Following on from the unexpectedly-controversial Part 1!

Hatchard’s Children’s Book Club

Hatchard’s, Piccadilly’s temple to books, has started a children’s book club. We missed the first one, but the new book is Shadow Creatures by Chris Vick, and you have until 27th June to read it and participate. From the website:

This is a gripping story set during the Second World War. It is unusual as it is set in Norway and Scandinavian folklore is cleverly woven into the plot. Based on the experiences of Chris Vick’s family, it feels more realistic than many war stories. Read it, be gripped and then write a review for us.

Write a short review (maximum 60 words) with your name, age and home town and send it to events@hatchards.co.uk by 27th June. Open to all ages – feel free to put your age as ‘over 21’. Two reviews will be chosen to feature in our shop newsletter and five lucky winners will be selected at random and sent a copy of the next book.

Amazon says ages 9-12.

More good books

I picked up The Clock Tower Ghost (1981) in a phone box library. I’d never heard of it, or its author Gene Kemp, but it’s a Faber Children’s Classic which is always a good sign.

The story is about a battle of wills between a bad tempered ghost and an equally unpleasant young girl. My children read it to themselves very swiftly, and loved it. My son said it was hilarious. Despite being a ghost story, it’s not spooky—neither child had trouble sleeping after reading it, which is always a plus!

Gene Kemp wrote many other books and was highly regarded. She won the British Carnegie Medal for The Turbulent Term of Tyke Tiler (1977, still in print), and was nominated for the Smarties Award four times, including for The Clock Tower Ghost. Tamworth Pig Stories looks good too, and would suit younger readers—Faber says 6-9 year olds. You can find more of her books on the Faber website. It may be easiest to track many of them down secondhand.

A sample from The Clock Tower Ghost:

“What we need is something really and truly horrific, like those spooky films,” announced Crook, and then wished he hadn’t because it took ages to explain to King Cole all about the cinema, moving films, television and so on. And it was clear that when he’d finished King Cole did not believe him.

“Just think of it as a magic lanterns,” said Crook, giving up. “And what we’ve really got to think out is what we do next. Dish-throwing frightened you more than it did them. Could you jump off the parapet more often?”

“Oh, dear me, no. It scares me stiff.”

“Well, it would,” said Crook. “No, it’s got to be something spectacular to frighten that girl. She’s tough.”

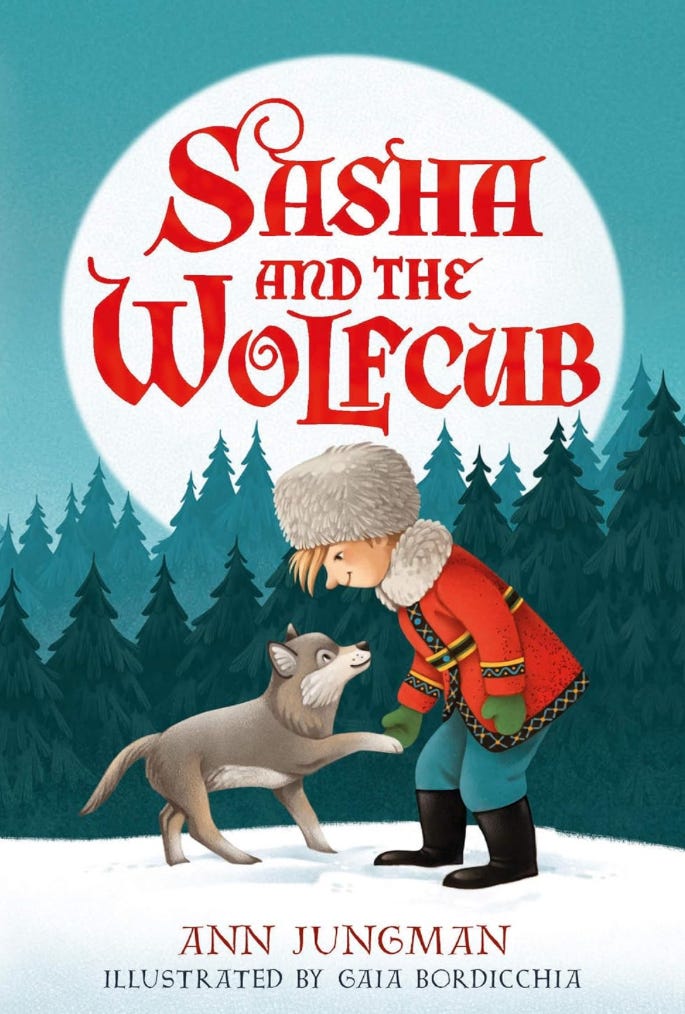

Sasha and the Wolfcub (1996) by Ann Jungman is a book we found in the library, and which my daughter insisted on reading cover to cover before we could leave. Faber (again) describe it as a rediscovered classic, and they’ve reprinted it with new, charming illustrations. There’s a sequel, Sasha and the Wolf, which we’re keen to get our hands on. Set in a Russian winter long ago, it’s about a boy and a wolfcub who discover they have more in common than they think. But can Sasha convince the rest of the village? It’s only 90 pages, with illustrations and large text. An ideal early chapter book for young readers but also an enjoyable quick read for older children.

From the opening:

It was winter in the village. This year, as every year, when the days shortened, snow began to fall until a thick blanket covered everything. Sasha stood on the porch of his wooden house and looked out at the vast white steppe, silent and mysterious. Sasha didn’t mind the snow because he had thick boots, a fur cap, and many layers of clothing to keep him warm. Like most children, Sasha liked it best when a blanket of snow covered the world, when all the rooftops had a thick layer of crisp whiteness and the trees had a canopy of silver snow that seemed to glisten magically pink in the setting sun.

A coda to the E Nesbit discussion

First, a reader kindly got in touch to draw my attention to Five Children on the Western Front, which I had vaguely heard of but hadn’t realised was written as a sequel to the Five Children and It stories. One of the things that makes my heart ache whilst reading Nesbit is thinking that her fictional characters would, if they were real, shortly have had to live through two world wars. I’m looking forward to reading this when I come to the end of my Nesbit spree. Be warned: my correspondent says you will definitely need tissues.

One commenter asked the following. If you have thoughts, please add them in the comments:

Thank you to the readers who took the time to share their views on removing inappropriate language from old children’s books. I was surprised at the strength of feeling the post elicited, and I appreciate those who made the effort to express their opinions nicely! I was partly surprised because I myself am very much in two minds on the question. I don’t like censoring, and I don’t want to rewrite history. But I also think childhood is precious and difficult subjects should be introduced with care. I think almost all of us can agree on those points.

When I was writing the post I initially included some thoughts on Edward Colston, the slaver and philanthropist whose statue was pulled from its plinth during the 2020 Black Lives Matter riots in Bristol. He has not been returned to his plinth, and now resides, still covered in red paint, in one of the city’s museums. Virtually all of the charities associated with Colston have removed his name from their branding. Although I obviously don’t want to venerate a slaver, I don’t think that erasing him from history is the right choice either. Maybe putting him in a museum means he’s still part of the conversation, but I’m not convinced.

Here’s part of what I wrote:

Chucking his statue in the harbour doesn’t undo the evils of slavery. I suspect it is more important to live with the uncomfortable truth that slavery was once a perfectly legitimate business which many people had no qualms about. Colston lived in a society which saw itself as advanced and civilised, just as E Nesbit’s did two hundred years later, and just as ours does today. Surely, a lesson we all need to be reminded of is that humans are weak to such evils. I’m not sure that wiping the slate clean as if these things never happened is a wise choice in the long term, even if it feels comforting right now. As Alexander Adams puts it: “By censoring the past we leave ourselves vulnerable to lies of the future.”

I didn’t include this in the published post. Perhaps I should have done, because it might have tempered the reactions of some readers to my suggestion that the n word should be removed from future editions of Nesbit’s children’s stories.

But although both examples, Colston and Nesbit, speak to questions of free speech and the judgement of the present on the actions of the past, I don’t think the comparison is hugely relevant, which is why I cut the paragraph. I understand that for some readers censorship in any form is unacceptable, and that includes deleting a single word from an otherwise delightful children’s book. But for me, we make those kind of censorship decisions for our children all the time. I haven’t told my children about all the horrors of the Holocaust yet, not because I’m trying to erase it from history but because it’s not appropriate for young children. When I read aloud, I skim over bits of stories that I know will upset them because they’re excessively gory or spooky, for example. I’m not suggesting we burn Nesbit’s books. There are millions of them in print, and the originals are free for all to read online. But I don’t think a child should be able to unexpectedly come across that word in a book published in 2017 that looks like it’s all about a magic castle.

Some readers made the comparison with Huckleberry Finn. I hope that regular readers know that I wouldn’t advocate for the censorship of Huckleberry Finn! But although the word is the same, the books are very different. Twain’s book has race at its very core. As Peter Messent, author of the Cambridge Introduction to Mark Twain, says, “[Twain’s] repeated use of that derogatory term in Huckleberry Finn is absolutely deliberate, ringing with irony.” Nesbit’s use of that term however, is not. Much as I love her, she’s no Mark Twain. She uses the word in the careless, throwaway sense that her characters would have used it. She’s not making a comment about anything. Removing the word from Huckleberry Finn (where it apparently appears 219 times) would entirely change the experience of reading the book. Removing it from The Wouldbegoods, where it appears once, wouldn’t make the slightest difference, but it would prevent an unsuspecting child from stumbling across it unprepared. The argument that young children stumble across inappropriate things all the time in the modern world does not seem to me to be an argument for leaving more of this stuff lying around to trip them up.

Of course parents should be talking about prejudice with their children, and of course encountering outdated attitudes in books is a useful opportunity to talk about how views have changed, and how we can confront them when they continue to show up today. But not every family is reading aloud and having thoughtful conversations, and these books don’t look like they’re going to contain anything problematic. It’s not like picking up The Diary of Anne Frank. Nobody is expecting the n word in this book:

For me, removing that word is not a slippery slope or the thin end of the wedge. We all agree the word is unacceptable—that’s why nobody actually used it in yesterday’s discussion. It surprises me that adults who would never write the word in an adult forum like Substack are happy to leave it in an otherwise innocent children’s book.

But I do understand that for some, principle is paramount and censorship of any kind is unacceptable. And I appreciate the American commenter who pointed out that it’s no surprise that many readers in the US have strong feelings on this topic at the moment.

Thanks to everyone who took part in the discussion. I do (mostly!) love hearing your opinions and how different families make things work for them.

Thanks for reading. If you’re not subscribed to How We Homeschool, sign up for free and never miss a post.

(Some of the links in this post are affiliate links.)

Re: conversations about difficult topics and bigoted views in children’s books—

First of all, my kids are young (preschool age), so ask me in 20 years whether this “is working”, haha. But what I’m currently doing is a multi-pronged approach.

- Some books, the juice is just not worth the squeeze, meaning whatever benefit we might get is not worth the amount or severity of objectionable content, so I will just avoid those titles altogether.

- Some books are read-alouds where it’s easy to edit on the fly or insert a quick explanation of why I don’t agree with the author or their character.

- Some books and topics I try to preload with more well-rounded perspectives. For example, before we started reading Little House, we read a number of books with more accurate history of Native people in the American Midwest.

Like I say, I don’t know how well this approach is “working” and I likely draw the lines in different places than others. But hopefully this is helpful to someone.

I’m very late to read and comment on this post but I find the discussion on removing problematic language fascinating. I simply don’t believe that there is anyone who doesn’t, at some point change the language of the books they are reading to their children. Words like fat, ugly, stupid, in books for young children, add nothing to the story and nothing is lost by simply omitting them. Children are sponges and if they hear you (reading Roald Dahl) describe someone as ‘enormously fat’ so will they!

Even when I read Dear Zoo, I change some of the he’s to she’s for balance!

This isn’t censorship, it’s just moderating language in the way I do every time I talk to children. Censorship happens at a government level, not in private homes and classrooms or even within publishers.

I’m a primary school teacher and again, this is what we do at school. Yes we have conversations around unacceptable language and outdated attitudes, but if you’re reading a book aloud in the last five minutes of a Friday in July, you take the path of least resistance and skip a word.

Interestingly, we’ve actually been asked by parents to stop stocking David Williams books in the school library as the content (and the author, frankly) contain such odious messages. I agree with them but it can be hard for schools to find a balance.