A reader got in touch recently, asking about the amount my children read and if I had any thoughts on how this had happened. It turns out I do!

Although I don’t understand how reading could be a genetic trait when written language is such a comparatively new invention, it’s true that my husband and I are both bookworms, so it’s not entirely surprising that our children are too. I understand that some people are just not that into books (although I don’t understand how!). Not all children are destined to be bookworms, and that’s fine, because the world needs more than people who can sit still for hours and forget to eat because they’re so engrossed in what they’re reading.

But what follows are some good principles to help move the needle. I would love to hear your own principles too!

1. Talk to your children

Your baby was listening to your voice before they were born. Once they’re out in the world, they’re still listening, and they love the way you sound. Every word your child hears is a word she will later read in a book. The more words she hears, the more context she has, the more those written words will mean to her, from the very beginning and more so as the books get more challenging.

So talk about what you’re doing, how you’re feeling, what you can both see and hear. Who’s coming to visit, how they’re getting here, why they’re coming. It doesn’t matter that your child can’t actually understand much of it in the beginning. Listening is how she’ll learn.

2. Read to them

You probably didn’t need to be told this one. Read aloud as much as you can and as much as your child wants. (Caveat: at bedtime we have always had a one-book-each rule. I don’t mean you should read until midnight. I mean if it’s a Sunday afternoon and all your child wants to do is listen to you read aloud from Little House on the Prairie, go for it. Sitting and listening to a read-aloud is fantastic for building concentration. If you google ‘children’s attention span’ you’ll see that a four year old can apparently concentrate for 8-12 minutes. Maybe in a noisy, busy classroom setting this is true. And maybe it holds true when concentrating on a tricky maths problem. But at home with a parent, a child who is spellbound by what they’re listening to can concentrate on it for a lot, lot longer.

(My own two have always been pretty happy just to sit and listen. I know a lot of home educating families let the children build with Lego or draw or do some other quiet activity while they listen. I think that’s totally fine so long as they are actually listening, which you’ll know from talking about what you read later. On which more, er, later.)

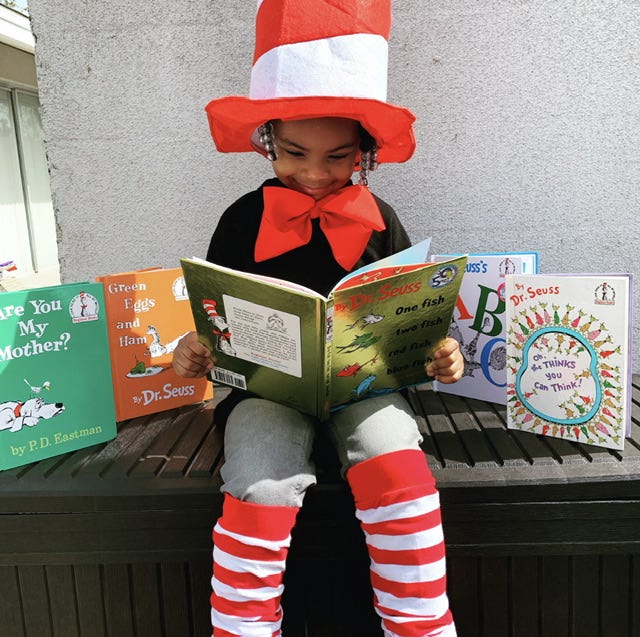

3. Have a wide variety of books

We have way too many books in this house. In fact it’s not a house but a flat, and sometimes the books are so overwhelming that I want to burn them all and replace them with four Kindles.

It’s not necessary to own so many books that you consider turning to arson. But I think it helps to have a wide variety. Picture books, chapter books, reading books, science books, history books. Biographies, nursery rhymes, poems, country guides, a children’s Bible and/or other religious texts. Silly books, serious books, books about animals and artists. The aim is for there to almost always be something that makes your child think “huh, what’s that about…?”

This is especially true when it comes to ‘reading books’, by which I mean the carefully-graded, progressively more challenging books children use when learning to read. I don’t think it matter which series you use, so long as you find one your child loves. Try as many as you can get your hands on until you find the series that makes your child immediately ask for more. (For us, it was Biff and Chip, which loads of children reportedly hate. So don’t worry about what your neighbour or friend recommends or rubbishes. The only judgement that matters is your child’s.)

You really don’t need to own a small library. Use your own public library and go whenever your children are tired of what you borrowed last. Always pop in when you walk past a second-hand bookshop. We have a free ‘phone box library’ near us (do these exist all over the world?) and I check it every week and sometimes more often. Usually there’s nothing for us, but sometimes there’s a gem.

4. Limit screens

If my children had unfettered access to screens, I’m pretty sure they’d never pick up another book. Screens are of course an integral part of the modern world. You’re using one right now and so am I. I’m not saying children should never use them. But how easy do you find it to pick up a book in the evening, when Netflix is always an option? And how easy do you find it to concentrate on that book when your phone is next to you, even if it’s not constantly pinging and lighting up?

We can give our children the enormous gift of removing the option and the distraction entirely. This doesn’t mean no screens, but screens at predictable times and in predictable quantities. I wrote a post on how we do screen time, but essentially each child gets to choose 20 minutes of TV after lunch, and that’s it. (Small amounts of Khan Academy or educational videos aside, always under my supervision.) It would never occur to them that I might turn the iPad on on a random Wednesday morning, or because they complained of boredom or because I needed some peace.

(By the way, we don’t own a real TV, so when the screen goes off the iPad goes away. I think it helps that the TV isn’t sitting there constantly, taunting the children with its presence.)

And if you’re reading this wishing that you had a different screen regime, but it’s too late and too hard to change: you can, and it’s not. Your children will, of course, complain bitterly. But if you hold firm for two or three days they will see this is the new normal.

Another caveat: I know parents of children with autism find that screen time can be very regulating and calming. I know next to nothing about autism and I’m certainly not telling you to take away a screen from your child if you know it is positively helpful for them. You know best.

5. Don’t keep your books too tidy

A place for everything, and everything in its place.

Ah, if only my children could absorb this message. It’s so simple, and yet our flat is a perfect example of how very, very difficult it can be to put into practice. I was going to list all the things I can see on the floor from where I’m sitting, but it’s too many to type.

But with books, I think this is no bad thing. You may have come across ‘strewing’, a homeschool practice of deliberately leaving interesting, tantalising things out and about for your child to stumble upon. The idea is that you don’t need to say “let’s read about geology!”, because your child will come to you with a collection of beautiful pebbles that you arranged in a small wooden dish on their ‘wonder table’, and a new book (in this instance, let me recommend The Pebble In My Pocket), and beg you to read it to her.

That’s how it looks on Instagram. I’m not on Instagram, and with good reason (see above: all the stuff on the floor). In real life, strewing means that there are at least four piles or stacks of books in our sitting room right now, there’s a stack outside the children’s room (it’s on its way to somewhere else), a book left open outside the bathroom, and books piled next to their beds. There are also books on their beds, in our bedroom for early morning reading, and in my rucksack which accompanies us on all trips out of the house. There are not currently books in the kitchen or bathrooms, but that’s not always the case.

In our case, ‘stumbling upon’ is literal. You might stub your toe. But it means that even if you weren’t actually planning on picking up a book, you might see Mr Wolf’s Pancakes, or Alexander the Great, or The Jungle Book, and you might just decide to flick through it.

Books obviously belong on bookshelves. But a neatly stacked bookshelf isn’t always very easy or enticing for little fingers, and those ‘front facing’ shelves take a lot of wall space and hold very few books. Embrace a few piles and stacks here and there, and see what happens.

6. …And don’t put them away too soon

Children don’t progress in reading in a smooth, linear fashion. It’s so tempting to put away each stage of reading book as your child moves on to the next. Don’t.

My children can now read chapter books to themselves. They rarely ask me for help anymore. I am desperate to put away the easier books that they no longer ‘need’, just to clear some space in our overflowing home. But I’ve noticed that they often go back to the easier books, and really enjoy them. Recently I realised that my daughter struggles with reading aloud, when she’s reading a challenging book. I think the effort of reading is enough, and trying to read aloud at the same time is just too much. But when she reads aloud from an easy reading book she does it beautifully. Going back to the easy books helps them to build fluency and confidence. It must be nice to be able to race through a story instead of laboriously wading through all the long sentences and dense pages of a chapter book, even if the chapter book story is more interesting. Susan Wise Bauer says ‘reading is simple’, and I think I would agree. But it’s also demanding, particularly when you’re reading at the edge of your ability. Keeping the easier books around means your children can keep reading even on the days they’re not up to Treasure Island or The Count of Monte Cristo.

Some reading posts I enjoyed recently:

with a reminder that if you spend all your time reading you can’t spend it on other things. on the best first lines in fiction. on how to Get Kids to Read for Fun.And some of my own previous posts that you might like:

How my children learnt to read, part 1 and part 2

Thanks for reading! If you’re not a subscriber sign up for free and never miss a post.

Excellent advice. I particularly like your recommendation to keep the easy books lying around. Children like going back to the easier books, not just because they are familiar and beloved, but because the experience of reading an easy, familiar book is so smooth; they feel accomplished, they feel they are good readers. Parents who take away the easy books as soon as they have been mastered are forcing their kids to always read books that they find hard. It's often well-meaning ("They aren't learning anything, rereading that old thing!"), but the message the children get is that reading is hard, and, worse, that they are bad readers (because it never becomes easy). Of course, learning IS hard. But the real reading experience, the experience one hopes to transmit to one's children, is the experience of easy, pleasurable reading. Of mastery of something difficult. And leaving them the easy books, to return to whenever they wish, gifts them that.

"...don’t worry about what your neighbour or friend recommends or rubbishes. The only judgement that matters is your child’s." Yes! Love this.

My 6 and 9yo still read their board books. I keep a small basket of the ones they treasured the most, and I'll find them reading them to each other, or to their dolls or stuffies, once in awhile. (And I've also noticed that my 6yo will grab one when she doesn't feel like slogging through her early readers or chapter books... it's almost as if she wants to read but her brain needs a break, so she chooses something below her level, that she basically has memorized, which of course serves it own purposes, too.) Thanks for making this point about easier books -- it's such a good one.