Special Guest Edition: How We Homeschooled Today by Latham Turner

On what can happen when you say “yes”.

It is all too easy to say No to our children’s ideas. (Or No’s best friend, Maybe Later.)

Lack of funds, lack of space, lack of energy. Often, we don’t even know how to do the thing they’ve suggested. And besides, there’s maths to learn and spellings to practice.

So I have endless admiration for

, former Navy Test Pilot, engineer, and entrepreneur, who said yes:I suggested maybe a project day every week. I told him he could pick the project and I’d help him with the ideas, tools, and execution. I even mentioned giving him rein on the power tools. What boy wouldn’t get excited about that? He smiled at me. Then the floodgates opened.

“Let’s do it! I’ve already picked out the first project. I want to build an airplane. And then you can teach me to fly. Let’s build this one.”

I had no clue how to build an airplane and it wasn’t exactly in the budget. It was barely in my imagination. My rational mind came up with a million reasons to say no. But this was our chance to do something exceptional. Something unique. This was my son asking to take control of his own learning. How could I say no? So together we’re going to figure out how to build (and pay for) an airplane.

Together we’re building an education.

You can read all about the project over at

, and I’m thrilled that Latham has given us a glimpse into his family’s homeschooling life.You can read previous guest posts in the Special Guest Editions tab on the How We Homeschool homepage. You’ll find more than twenty accounts of home education around the world, and if you don’t think your family life is represented, I’d love you to write your own! Latham found

’s homeschool posts really useful, so you might like to take a look at Ruth’s guest post if you haven’t read it already.When Catherine asked me to share my experience and a “day in the life” of our homeschool, my heart rate immediately spiked and my palms started sweating. This was surely the moment when I would reveal to the world that I didn’t know what I was doing, and that even the most ambitious plans can and do go awry. I had a good little freakout, and then I took a deep breath, just as I model for my kids. After my brain finally stopped imagining every worst case scenario, I found myself excited to share. But share what exactly?

The question of why we got started homeschooling is an easy one. I got started because I didn’t know what else to do as I watched my son fall further and further behind. My son, aged 9, has Autism Spectrum Disorder, and every school system we tried had undervalued his learning. “He’s doing as well as can be expected.” “He just isn’t going to be a reader.” We’d heard it all, but I refused to listen. Instead of giving up on my son, accepting his “disability” as fate, I insisted that he was capable of more. And when no one took me seriously I did the only thing I could imagine trying. I took his education into my own hands.

But the question of how we homeschool is that much trickier.

My answer has changed so many times. When we started homeschooling, I followed a classical model. I would wake up before my son and write the day’s plan on our little whiteboard. A typical Monday looked like:

Reading (45 minutes)

Writing (25 minutes)

Math (40 minutes)

Literature (40 minutes)

Latin (30 minutes)

History (35 minutes)

We’d gather around our kitchen table, I’d start a timer on our iPad, and we’d begin a lesson. As soon as the lesson was done, he would race off for a body break, which usually meant hugging the dog and occasionally meant throwing his football around. Maybe we’d quiz some Latin flashcards during that time, but often he needed a break. 20 minutes later, rinse and repeat.

My plan for this year looked pretty much the same. I dropped the time constraint, and instead planned lessons in our math curriculum, or a chapter in our book. But by the third day, my son revolted. He refused to continue, and his almond brown eyes stared at me with an intensity I thought only gladiators and pilots knew. I sat in shock and fear, trying to hide the seized gears where my brain should have been.

It took us a few days, days where we didn’t do school, where he didn’t even talk to me, and where I tried my best to set an example of mature response but continually found my willpower lacking. Eventually we found our way. So now we have a new routine.

Every Sunday I create an assignment sheet for him. On a one page Google Doc, I detail the assignments I expect him to complete this week. They may be worksheets, puzzles, a recital of a poem he’s working on, chapters to read, chess positions to learn, or drawing exercises to complete. Everything is chosen to make sure he’s pushing himself. But the total amount of work is not too much—after all he needs lots of free time. That gets printed and is his for the week.

Every day, from 9 am until noon, we have project time. Right now we’re building model boats. His first popsicle stick boat sank, so we’re trying to understand what went wrong. This morning we’ve created 5 test rigs: popsicle sticks glued together with different types of glue, and we’re about to test them. We grab our rigs, a stopwatch, and a Pyrex dish, and we head to the bathtub. He fills the pyrex with water, submerges the first rig, sets the timer, and waits. Two minutes later he’s eagerly pulling the rig out and inspecting it. The cosmic glue has chipped off and he declares that it’s eliminated. He’ll repeat this again and again, until finally the hot glue is declared the best glue for our next boat.

We note the results in our project notebook, take an obligatory picture, and clean up.

These project days can seem like play some days, and other days they feel like a grind. I’m convinced both types of days are important. I want my son to follow what excites him. I want him to learn to take action. And I also want him to get stuck, to feel what it’s like to not know what to do, to brainstorm ideas with me, and to ask for help. I don’t care how he’s tracking against state standards, but I care how much passion he shows and how much rigor he applies to his own thinking.

After lunch is his time to work on assignments. He can do as many or as few assignments as he wants, but they all have to be complete by Saturday evening. Today he chooses to do all his grammar assignments. He’s loving Beowulf’s Grammar Workbook, so getting him to complete 4 assignments is easy. After a break to play baseball, he reads a few pages of Beast Academy Math. He’s not understanding how to solve one of the practice problems, so he asks for help, and I teach the material to him. I’m always sitting next to him, so it’s easy to teach when he needs support, and he picks up the material quickly today. The puzzles are hard and he’s getting antsy, so he decides he’s had enough for one day.

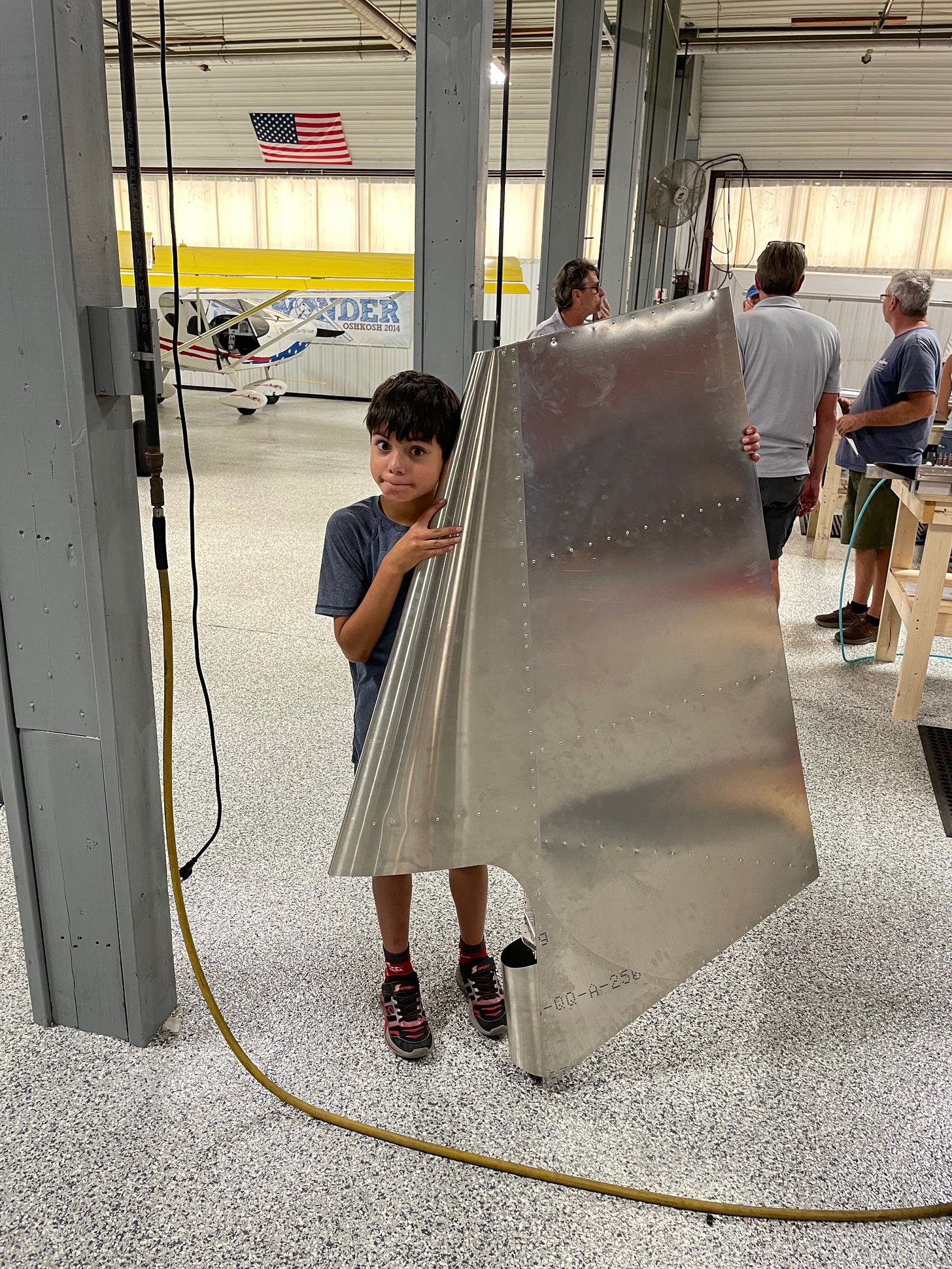

Then last week we threw another wrench into our schedule. We flew to Mexico, MO, home of Zenith Aircraft, and spent two days learning how to build an airplane. My boy read schematics, learned how to use the tools, applied clecos1, and popped nearly 300 rivets using a pneumatic rivet gun. He had a blast. The team at Zenith even took him up in the cockpit of one of their airplanes and let him fly! By the end of the two days, he had a fully built, shiny metal tail and even more conviction that this was his project. Now we are figuring out how to afford the full airplane, a problem which I’ve tasked him with helping me solve.

I’m not sure how the plane will fit into our schedule going forward. Project time may become airplane building time every day. If we build for 12-15 hours a week, we should be able to have a working airplane in 30 weeks. I’m not quite sure we’ll go that fast, and I also enjoy doing other projects with him. The airplane may become a weekend project if he decides that he wants to also build other projects. And if he finishes his weekly assignments early, we may have a free Friday to build all day. Those are all questions we’ll solve when we come to them.

Until then, my son is even more excited to build this airplane. Like everything in homeschooling, we’ll figure it out together.

I asked Latham for his advice to parents who are envious of his engineering experience. I wondered if there might be a book or a YouTube channel he’d recommend, but he has some much better, ‘real life’ advice:

I’ve learned to be comfortable looking foolish and asking ‘dumb’ questions. It’s a trait I hope to pass on to my children as well. I wouldn’t say I feel confident as an engineer or that I learned it through school or books, but I spend a lot of time asking the smartest people I can find a lot of questions and genuinely caring about them when they can teach me something.

Thank you again to Latham for sharing his ‘day in the life’. Do take a look at his Substack, Building the Plane, and subscribe to see how they progress.

Thanks for reading. If you’re not subscribed to How We Homeschool, sign up for free and never miss a post.

Clecos are temporary fasteners used to hold metal together before it’s riveted or welded. They’re a key component of building an airplane.

Wow! Thanks so much for sharing this! As a fellow parent of a young man on the spectrum, this is especially inspiring!

Love this story.