We live in a world where easy is good. We like life hacks and easy meals and non-iron shirts. The twentieth century was all about making life easier. Just in the realm of the home, we now have washing machines, electric irons, microwaves, vacuum cleaners, dishwashers, shop-bought bread, refrigerators. To read Little House on the Prairie is to be constantly amazed by how much work Ma and Pa had to do simply to keep everyone fed and clothed and sheltered.

Life for our children too, though they would strenuously deny it, is unbelievably easy. For millions of children, having clothes and shoes that fit and keep you warm is unremarkable. A varied diet, a plethora of toys, playgrounds, cosy beds (free from bedbugs), and no expectation that they need to earn any money, either for themselves or for their family—all these things are par for the course. I know that there are still many families who don’t live with these comforts, and that many children do not feel safe and secure, and I don’t deny these people’s experiences. But overall, the vast majority of us have a much easier time of it than we would have done at any other time in human history.

explores the ramifications of our easy lifestyle in his book The Comfort Crisis. He quotes Dr Marcus Elliott:“Over our species’ hundreds of thousands of years of evolution,” Elliott said, “it was essential for our survival to do hard s*** all the time. To be challenged. And this was without safety nets. These challenges could be from hunts, getting resources for the tribe, moving from summering to wintering grounds, and so on. Each time we took on one of these challenges we’d learn what our potential is.”

Elliott goes on to explain that if our potential is one big circle, most of us are living in a tiny space at the centre of that circle. “We have no idea what exists on the edges of our potential. And by not having any idea what it’s like out on the edge… man, we really miss something vital.”

Challenge is good for us. Easter cites a study by Mark Seery, PhD, of people who either had or had not experienced stressors, ‘like a serious illness or financial difficulty, death of a loved one, violence, floods, earthquakes’ etc:

Compared to the people who’d been sheltered their entire lives, “the people who’d faced some adversity reported better psychological well-being over the several years of the study”, said Seery. “They had higher life satisfaction, and fewer psychological and physical symptoms. They were less likely to use prescription painkillers. They used healthcare services less. They were less likely to report their employment status as disabled.” By facing some challenge but not an overwhelming amount, these people developed an internal capacity that left them more robust and resilient. They were better able to deal with new stressors they hadn’t faced before, said Seery.

Easter also suggests that one reason for the soaring rates of the ‘diseases of despair’ faced by adults and children alike in modern society—depression, anxiety, addiction, and suicide—is, perhaps counterintuitively, the very ease and safety of modern life. “We lack physical struggles […]. We have too many ways to numb out, like comfort food, cigarettes, alcohol, pills, smartphones, and TV. We’re detached from the things that make us feel happy and alive, like connection, being in the natural world, effort, and perseverance.”

How safe are our children?

Child mortality has plummeted, but as parents we are ever more vigilant for our children’s safety. Children only a generation ago used to roam with extraordinary freedom. Now it feels negligent to leave them in the garden by themselves. Letting your 8 year old child play unsupervised within view of your house can invite a police response. Michael Easter has an explanation: problem creep. Humans have evolved to spot problems and threats. There are now many fewer threats for us to spot—no sabre-tooth tigers, or frozen winters without shelter, or food sources disappearing. But we’re programmed to find problems, so that’s what we do. There are scary things facing our children (careless drivers, or pornography freely available to any child with a smartphone, for example), but overall our children are much, much safer than at any other time in human history. And yet I bet I’m not the only one who lies awake at night worrying about all the threats my children face.

If you know someone who might like this post, please feel free to share it.

And when there is an opportunity to face a challenge, we find it very difficult as parents to let our children struggle. We are evolutionarily programmed to smooth the path for the next generation. Personally, I am terrible at letting my children get on with something difficult unaided—at the first sign of struggle I leap in to help them out. I know it’s not the right thing to do, but I find it an almost impossible urge to overcome.

The evolutionary instinct of a mother to protect her young makes sense in a dangerous world. But in a world of health & safety and bike helmets and suncream? I wonder if this instinct has become a bit like our instinct to feast on food when it’s readily available. Now that food is always readily available, that instinct isn’t particularly helpful.

And our predisposition to spot danger can lead us wildly astray. How many parents have you seen in the playground, repeatedly imploring their children to be careful? “That’s too high!”. “That’s not safe!” “Please come down from there!”. “Be careful!”. Meanwhile we happily strap them in the car dozens of times a week. But

, a developmental psychologist, points out that in Canada between 2007 and 2022, there were two deaths from falls in the playground, compared to 480 deaths from motor vehicle crashes (with children as passengers). And there were precisely zero deaths from children falling from trees. (It’s almost like we’re… primates.)This isn’t just about the great outdoors. I feel this influence in the education of my children, too. They don’t want to struggle, of course—who does? When a problem is too hard, they quickly give up and switch off. I work hard to give them work that is just challenging enough to help them develop their skills, but not so challenging that they’re put off forever (that magical ‘zone of proximal development’). And at 6 and 8, they’re still very young to be working through deep and complex problems unaided. But when you do work at a really difficult problem, you derive enormous satisfaction from the progress you make. Every scientific breakthrough (including all those household conveniences) takes tremendous trial and error, many iterations that didn’t work out, thousands of hours of dogged hard work in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges. Last week the children and I read that in 1895 Lord Kelvin—a very smart cookie—declared that ‘heavier-than-air flying machines are impossible’. Luckily the Wright brothers didn’t mind the word ‘impossible’—8 year later, they flew the first aeroplane.

I’m not advocating for children returning to sweeping chimneys or eating nothing but bread and butter for half their meals. I don’t think we should seek out dangerous diseases or move to earthquake-prone regions. But I do think that all this ease and convenience makes us timid. There is so little challenge in our lives, and in our children’s lives, that we forget how good a challenge can be. And it’s not easy to know how to build challenge into their lives, or ours, in a world that has become both progressively safer and progressively challenge-averse. For some ideas, have a look at Let Grow, which is working to try to reverse the steady erosion of our children’s freedom. And if you’ve found ways to incorporate some risk and independence into your children’s lives, I’d love you to share it in the comments. Bonus points if you’re a city-dweller.

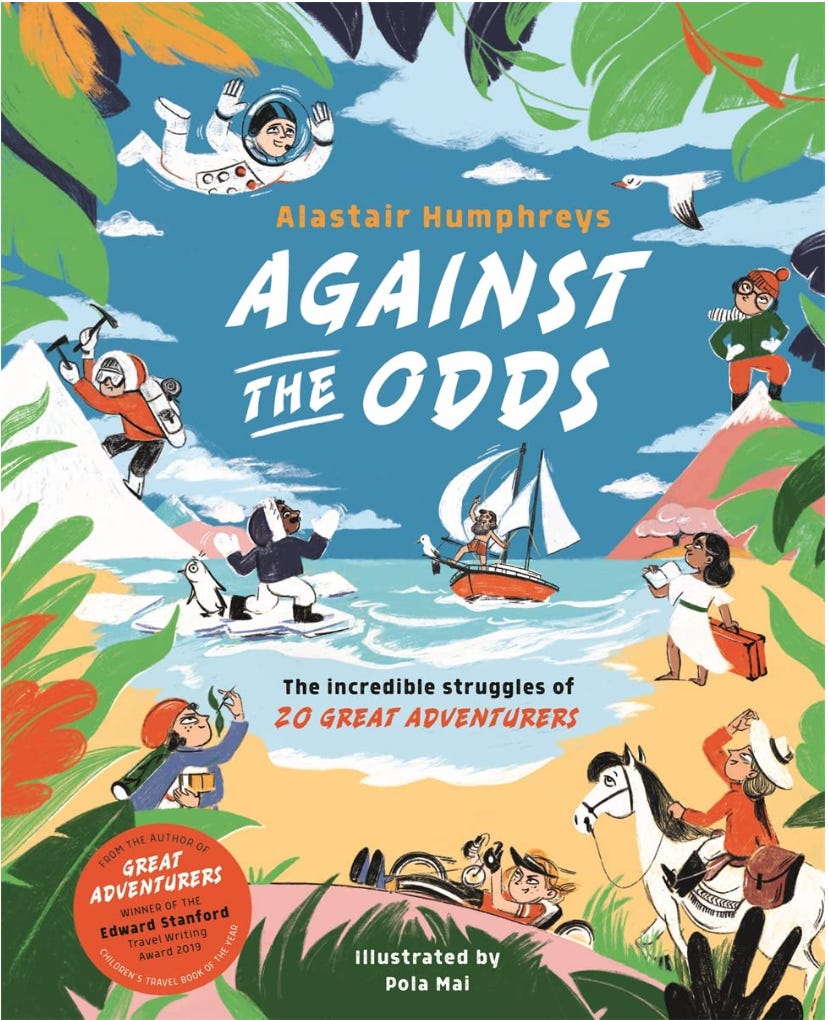

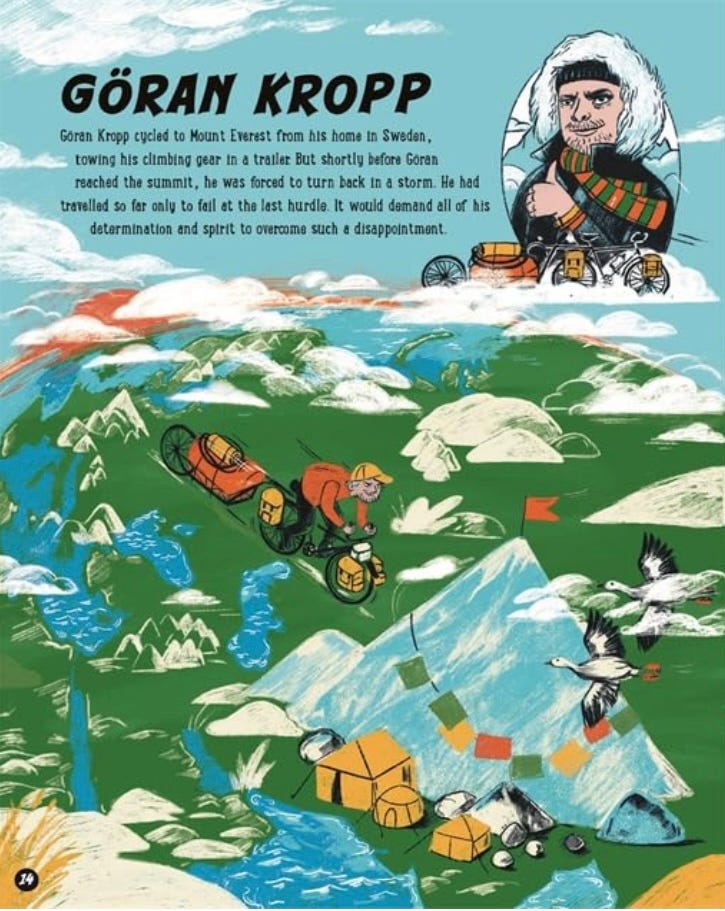

All of this is why I am enjoying Alastair Humphreys’ new book, Against The Odds, so much. A year ago I wrote about one of Alastair’s earlier books, Great Adventurers, which I think every family should own. Against The Odds is essentially a ‘Part 2’, but it has an added edge to it. The title is well-chosen. These aren’t just explorers who undertook incredible expeditions. Even more than the first book, this one is filled with people who completed their challenges in the face of seemingly insurmountable difficulties. There are adventurers with paralysed or amputated limbs. Women who explored at a time when women were supposed to stay at home and were literally arrested for wearing trousers. African Americans who stole Confederate ships or explored the Arctic despite being born only a year after the abolition of slavery. Friends who travelled the world in the face of oppressive Communist regimes. Some of the subjects found themselves in peril almost by accident, but many actively chose to put themselves in extraordinary situations. In a world that is geared towards making things easier, it’s startling to read about people who deliberately choose to make things extremely difficult, over and over again. There are lots of examples of people making mistakes, or facing setbacks, and choosing to carry on. These are not superheroes. They’re real men and women.

The book is a great jumping-off point for exploring other subjects, like geography, history, and science. I originally wanted to share the book with my children (and with you!) because it’s one of those books that is marvellously educational simply as a by-product. But this book is so much more than a way to learn about other countries or historical periods.

It’s not that I particularly want to encourage my children to trek across desert war zones or travel into space, but reading about what the human mind, body, and spirit are capable of is truly inspiring. When everything is served up to you on a platter, as so much of our lives is today, you forget how much you can do for yourself, and how very good it feels. Reading a book about adventure is not the same as going on an adventure yourself, but it’s not a bad place to start. It might inspire you to invite just a little risk, a little discomfort, into your life, and expand that tiny circle of comfort at the centre of your potential.

Thanks for reading. If you’re not subscribed, sign up for free and never miss a post. Readers get regular ‘how we homeschooled today’ posts, guest posts from home-educating families around the world, and occasional longer pieces like this one. Come and join us!

(Just so you know, a couple of the links in this post are affiliate links.)

This is all so very true.

My eldest hates, and has always hated, facing challenges. She finds that so many things come naturally to her, when something is initially difficult she will drop it immediately. She has been this way since she was a baby. It’s very frustrating as a parent! Often she comes back to something and somehow, without putting in any work, she has mastered it. Other things never get started (learning to ride a bike) or progress is slow (learning to read). She also lives a very comfortable life and thinks money grows on trees. I’m sure I’m not alone!

For independence, our local Home Ed group is brilliant. There are enough parents around the park and cafe that all the kids roam freely. I check regularly that she’s still on site, but otherwise she has three blissful hours of freedom. It does her the world of good.

Thanks for this. I have Easter’s book, but haven’t read it yet. I’m now encouraged to get on with it!