In the UK, the Labour Party are pushing to create a register of children not in school. The Conservative government are also in favour of this, although apparently with less urgency: “We are committed to legislation for a children-not-in-school register and have committed to progress with this when legislative time allows.”

At the moment, if a child has never been on a school roll, parents are under no obligation to inform the local authority that the child is being home educated. If a child has ever been in school, the local authority will know about them because they have to come off the school roll, at which point the powers that be want to know where that child will now be educated.

Many home educators are strongly opposed to the idea of a register. Possibly those in favour just keep very quiet, but there is certainly a vocal, organised network of parents who don’t want it and are prepared to fight it every step of the way.

There are two aspects to the question for me: first, how it will affect me and my children. And second, how it will affect everyone else. I know I’m doing a good job with my two. I value education, and I spend a lot of time and effort making sure my children’s education is the best it can be. I don’t need or want some government agency asking me to fill in forms to prove it. I really don’t want my children to be subjected to a total stranger assessing them to decide if their education is good enough. Ugh.

But this isn’t just about me. I’m ok with the idea that the state should act as a backstop when it comes to children’s care. But I don’t think that a register is a straightforward way to achieve that. I think the idea of a register raises several critical questions that have to be addressed before the register is created.

Confusing two different things

If a parent chooses not to send their child to school and chooses not to give them a good education at home, that child needs help. And if the child has never been to school, the state has no way of knowing that they exist, which obviously makes it difficult to help.

But there’s a confusion here. If a parent has no intention of home educating, but also doesn’t bother to send their child to school, do they belong on the home ed register? Would they even sign up to it? Similarly, although there seems to be a connection, what, actually, has persistent truanting got to do with home ed? These two things are almost always conflated in discussions of a home education register. Here’s a quote from a recent piece in the Guardian:

A Labour government would legislate for a compulsory national register of home-schooled children as part of a package of measures designed to tackle the problem of persistent absence in schools in England.

My children are home educated. They’re not persistently absent from school. If you don’t go to a party you weren’t invited to, you did not fail to show up. The same article notes that 21% of school pupils miss 10% or more of their lessons. 1.56 million pupils in England in autumn and spring 2022/23 fell into this category1. These are pupils—not children missing from education. Pupils on the school roll, missing 10% or more of their lessons. A problem, for sure, but those children are not home educated and don’t belong on a home ed register.

How do we decide if a child is receiving a suitable education?

As things stand, home educating families don’t have to follow the National Curriculum, or any curriculum at all. The wording in the current draft guidelines is vague:

The parent of every child of compulsory school age shall cause him to receive efficient full-time education suitable – (a) to his age, ability and aptitude, and (b) to any special educational needs he may have, either by regular attendance at school or otherwise.’

— Education Act (1996)

And

even though there is no requirement to follow the National Curriculum or other external curricula, there should be an appropriate minimum standard which is aimed for. The education should include sufficient secular education enabling your child, when grown-up, to function as an independent citizen in the United Kingdom beyond the community in which they were brought up.

That, essentially, is it. As a parent, it affords me enormous freedom, which I love. My children learn Ancient Greek, which is of no value in terms of the National Curriculum. They spend hours playing maths games but very little time on the maths worksheets which would neatly demonstrate their abilities to an outsider. My six year old can read The Hobbit to himself but is struggling enormously with his handwriting. If he were at school I have no doubt it would now be A Concern, but at home it doesn’t have to be. But what would a Home Education Officer have to say about it, would it mean my son was failing to meet an ‘appropriate minimum standard’?

And where is the small army of education professionals who can decide whether children ranging from 5 to 18 years old, covering the whole spectrum of learning needs, are receiving a suitable education? Assuming that army exists, what criteria are they using to assess our children? The joy of home education is that every child is treated as an individual. But bureaucracy doesn’t deal in individuals. There are already 86,000 home-educated children who are known to the local authority—the real number is significantly higher. That’s a lot of children to assess on a case-by-case basis. I fear that the creation of a register will be swiftly followed by the introduction of educational standards that home-educated children must meet. How else will the Home Education Officers be able to say whether a parent is doing an acceptable job? How do you assess whether children are meeting standards when they are all doing such different work at home?

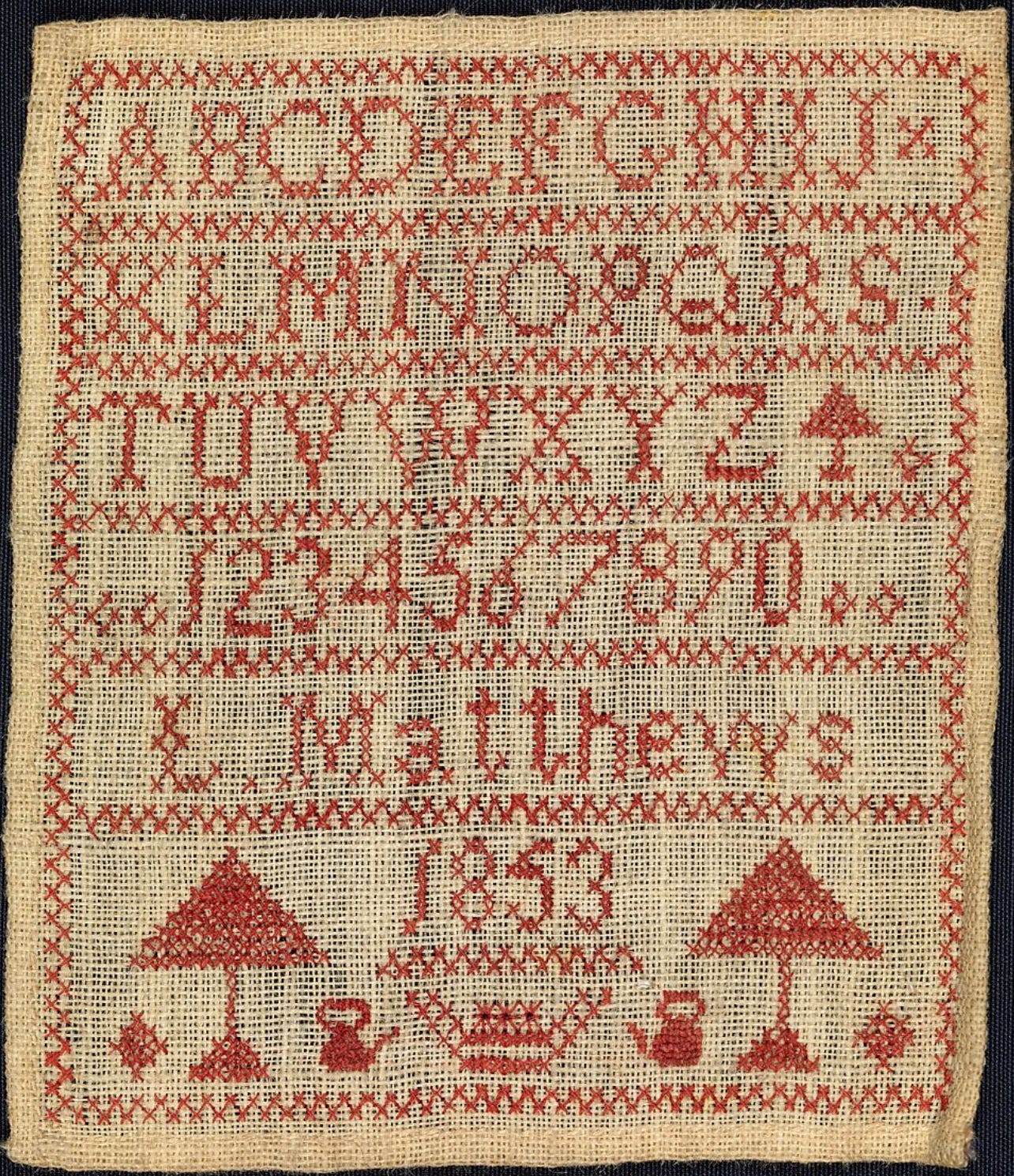

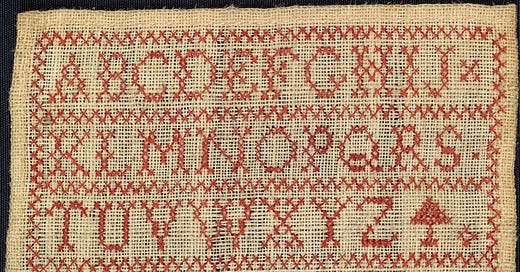

If I ever take up cross stitch, Baroness Hale’s opinion will be top of my stitchable quotes:

In a totalitarian society, uniformity and conformity are valued. Hence the totalitarian state tries to separate the child from her family and mould her to its own design. Families in all their subversive variety are the breeding ground of diversity and individuality. In a free and democratic society we value diversity and individuality. Hence the family is given special protection in all the modern human rights instruments including the European Convention on Human Rights […]. As Justice McReynolds famously said in Pierce v Society of Sisters 268 US 510 (1925), at 535, “The child is not the mere creature of the State”.2

If you know someone who might like this post, please feel free to share.

Are home educated children safe?

A school child will be seen almost daily by multiple adults, who might therefore notice signs of abuse or neglect, but a homeschooled child might not. There’s a murky suspicion that home educated children are ‘invisible’, that they spend all day at home and never socialise with anyone outside their own families. Of course for the vast majority of children this is nonsense. More than a day spent at home has my own family climbing the walls! My children see friends, extended family, librarians, opticians, Scout leaders, bus drivers and so on. They are far from invisible. But they don’t see the same schoolteacher day in and day out, because their teacher is me. Of course, this does theoretically mean the opportunity for child abuse in home educating families is greater. And, reflecting this, home educated children are already twice as likely to be referred to Social Services compared to schoolchildren and children under 5. But guess what? After the referral they are significantly less likely to have the child made subject to a child protection plan. So even without a register, home educated children are already more likely to be referred, and then less likely to have any action taken.3

Illegal faith schools are another area of concern. Humanists UK estimates that around 6,000 children in the UK are being educated in these schools. These schools claim to offer only part-time tuition, and teach only a very narrow, religious curriculum, and claim their pupils are home-educated.

This allows them to avoid the need to register as schools with the DfE. However, in actual fact, many of the pupils at these settings will be attending them full-time. This means the religious instruction they are receiving is their only form of education. Nevertheless, because there is no register of home educated children, the DfE and local authorities (LAs), who are responsible for ensuring that all children receive a ‘suitable’ education, have no way of verifying whether these children are really home educated nor of compelling the schools to register if their pupils are actually full time.

These institutions manage to avoid being classed as ‘schools’, which would obviously involve scrutiny, and because there is little scrutiny over home education their pupils manage to fall between two stools. But is a register of 86,000+ children the best way to identify the 6,000 children in illegal faith schools? We already have an Unregistered Schools Taskforce. Is it not possible to close the loophole that allows these institutions to operate under the radar? In England even a childminder looking after a single preschooler has to be registered with Oftsed (the national schools inspectorate) and provide evidence to Ofsted of the care they provide. Ofsted inspect 10% of childminders at random. If every childminder already has to be registered, why not every institution providing some form of childcare, which would cover the illegal faith schools. This is not a home education problem.

Not the only priority

If the Home Education Officer decides your child is ‘behind’, will the child be sent to school? Let’s not forget that in 2022, 41% of Year 6 pupils (the end of primary school, aged 11) failed to meet the expected standards in literacy and numeracy. That’s 275,000 school children, failing to meet the government’s own standards, in a single year. I can’t help feeling that the enormous resources required to create and monitor a national register of home-educated children would be better spent on the school children that we already know are being failed by the system.

Outside school, what about the thousands of children on waiting lists for mental health services? In Blackpool, to give one tiny example, children have to wait four months or more for an appointment. At the end of last December, 45% of referrals waiting to be seen in Blackpool had been waiting longer than 18 weeks. Those will be almost overwhelmingly school children, desperately in need of support. Some of those children will be showing up in the ‘persistently absent’ data. Wouldn’t they be better served by investment in mental health services than the creation of a home ed register? (I know the two aren’t mutually exclusive, but we’re always being told there’s no magic money tree. So if we have to spend the money in just one place, I’d much rather it was the mental health services.)

Is this really about supporting families?

The discussion about home education is always cloaked in the guise of government wanting to support families, protect children and ensure they receive the best education. But if this is true, why do home educating families have to pay for their children to sit public exams? You’re not legally obliged to sit GCSEs (usually at age 16) or A-Levels (age 18), but for many careers it’s a requirement, and working towards these qualifications is a significant educational undertaking. Sitting GCSEs costs up to £50 per subject: I took 10 GCSEs when I was at school; some children sit even more. That’s £500 to sit the exams that school children take for free. (And to be clear, that doesn’t buy you the text books—that’s just the cost of sitting in the exam hall and taking the exam paper.) I recently learnt that deaf children in schools are provided with support through a Teacher of the Deaf. But if you opt to home educate your deaf child, you’ll no longer be eligible for that support. If you’re lucky, a charity will provide financial support. But the government, who professes to be concerned for the welfare of all children, washes its hands of you once you exit the school system.

What do you think?

Readers of How We Homeschool come from all over the world and state approaches to homeschooling vary hugely from country to country. I’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences on the benefits and pitfalls of home education registers and increased state involvement, and how you manage the requirements with your own family. Please share in the Comments.

Thanks for reading. If you’re not subscribed, sign up for free and never miss a post. Readers get regular ‘How we Homeschooled Today’ updates, guest posts from homeschoolers around the world, and lots of book and resource recommendations—and sometimes discounts too! Come and join us!

This information comes from the excellent Home Education and the Safeguarding Myth: Analysing the Facts behind the Rhetoric, from Education Otherwise.

Excellent essay! The remarkable aspect of this whole discussion is that state controlled education is assumed by many as the default... rather than, as has been the case historically, the exception to the norm. It is as if all that stands between children plummeting into an abyss of ignorance and dullness is a platoon of nameless government bureaucrats and their clipboards.

I think it was G.K. Chesterton (though I can't find the quote??) who remarked on the redundancy of State education. 'twas something like: You [who argue for it] are like the fool who stands in the rain, under an umbrella, to water the flowers.

In Australia we are required to register as home educating by the time a child turns six. Each state has different stipulations to be adhered to, where we live in Victoria it is probably the most relaxed with no testing or benchmarks required, though a plan of how we plan to address the key areas of the Australian curriculum is required as a once off. We don't receive any benefits from the government as elective homeschoolers in Australia (that I am aware of anyway!) Last time I checked it costs the government $20K to school one child per year and yet there is no financial support provided to homeschooling families. I wonder does the UK provide any support or plan to if they succeed in setting up a register?